🏴 Scotland: The Debate Around Independence

The Scottish National Party was always expected to win the most seats in this election, and Nicola Sturgeon returning as First Minister comes as no surprise.

The final results show the SNP won 64 seats - an increase of one seat from the 2016 election, but one short of an overall majority.

Predicted results are rarely considered newsworthy, but the implications of a pro-independence majority lead to one question - for how long can Downing Street delay and deter?

As this conversation undoubtedly continues, below is an overview on some of the key aspects of this debate. I hope you find it an enjoyable and informative read.

Until tomorrow,

Hilary

*This piece was originally published on May 9, 2021

WHAT DOES SCOTLAND LOOK LIKE?

Admittedly, it’s all a bit confusing. Yes, Scotland is already a country. However, it’s not an independent country - along with England, Wales and Northern Ireland, Scotland is part of the sovereign state of the United Kingdom.

There are currently about 5.4 million people living in Scotland. This accounts for just over 8% of the UK’s population.

Of that Scottish population, an estimated 10% were not born in the UK. The majority of them are from EU countries (mostly Polish), while 44% are non-EU nationals.

While Scotland only accounts for 8% of the UK’s population, it actually makes up almost a third of the UK’s land area - including more than 790 islands.

Scotland operates a completely separate legal system to the rest of the UK.

It shares a 96-mile long border with England.

BACK TO THE BEGINNING

King James VI (6th) was just 13 months old when he became King of Scotland, after his Mother - Mary Queen of Scots - was forced to abdicate. At the time, the kingdoms of England and Scotland were completely separate.

By 1603, King James was 36 years on the throne. That same year, Queen Elizabeth I of England - a relative of his - died unmarried and childless. As a result, James VI of Scotland also became James I of England, and was monarch of both. This was known as the “union of the crowns”.

Despite his best efforts, King James failed to fully unite the two kingdoms - they might have had the same monarch and army, but there were separate parliaments and laws. More than a century passed until the Act of Union in 1707, which created the United Kingdom of Great Britain.

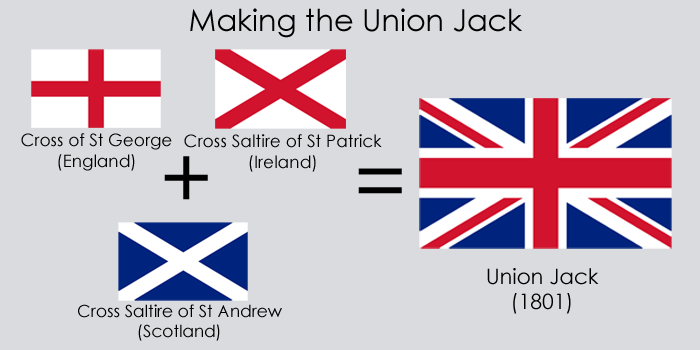

Side note: It was under the rule of King James that the British Flag, also known as the Union Jack, was created. Both the crosses of St Andrew (Scotland) and St George (England) are featured, along with the cross of St Patrick. The reason it is sometimes referred to as the Union Jack stems from Jacobus, the latin version of James.

DEVOLVED GOVERNMENT

In Scotland today, much like in Wales and Northern Ireland, there is a devolved government. Scotland’s parliament - based in Holyrood - have control over certain issues, while other decisions are still made in Westminster.

That devolved government has been in place since the late 1990s, but the first significant push for it was two decades prior.

In May 1979, there was a referendum on the question of ‘Home Rule’ in Scotland. A slim majority of 51.6% of voters were in favour of it. Despite this, the bill was quashed because of a low voter turnout - those who voted yes accounted for less than a third of the electorate, failing to meet the required threshold of 40%.

Anyway, by 1997 Scotland voted in favour of a devolved government by 74%, paving the way for Scotland to have its own parliament for the first time in nearly 300 years.

Key to this was the Scotland Act 1998, and the devolved government’s first meeting was in May 1999.

Scotland’s parliament is made up of 129 MSPS - Members of the Scottish Parliament. This is where the number of 65 MSPs needed for a majority comes from.

Who has control over what?

Scottish parliament;

- Agriculture, forestry and fishing

- Education and training

- Health and social services

- Environment

Westminster;

- Immigration

- Foreign policy

- Defence

- Employment

Crucially, the 1998 Scotland Act states the makeup of the union is a matter reserved to Westminster. This means the power to call an independence referendum does not lie with the Scottish government.

POLITICAL DYNAMICS IN SCOTLAND

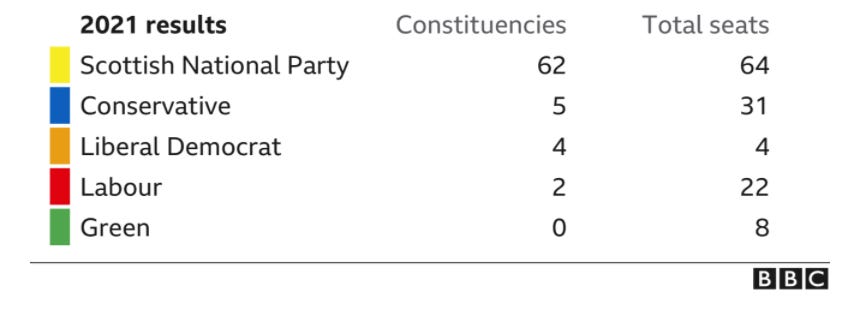

As mentioned, 129 MSPs make up the Scottish Parliament. This weekend’s results show the SNP with one seat short of an overall majority.

It was the highest ever voter turnout in a Scottish parliamentary election, with 63.2% of the electorate casting a vote.

To give context to how much the SNP dominates at the moment, they won more than double the amount of seats as the second-strongest party in Scotland, the Conservatives.

The Green Party - who won 8 seats - are Scotland’s other pro-independence party, and supported the SNP in the last minority government.

Worth noting: In what can be interpreted as a further indication of the SNP’s political dominance, Scotland’s voting system is specifically set up with the intention of preventing one party winning an overall majority.

How so? Well, the 129 MSPs are elected in different ways. 73 of them are elected from each of the 73 constituencies in a first past the post method. This is the same system used for elections in Westminster. However, what this method can mean is that more voters in a constituency could vote against the victorious candidate rather than for them.

The other 56 regional MSPs are elected based on a second vote, where the electorate vote for a party rather than a specific candidate.

The SNP’s manifesto ahead of this election was abundantly clear - “we are seeking the permission of the Scottish people in this election for an independence referendum to take place after the crisis (pandemic).”

2014 REFERENDUM

The problem is, SNP leaders repeatedly acknowledged the independence referendum in 2014 was a “once in a generation” event.

Back in September 2014, 55% voted against independence, while 45% voted in favour. There was a significant voter turnout of 84.59%.

Weeks before the vote, the UK’s Prime Minister at the time, David Cameron, promised more devolved powers if a majority voted in favouring of staying within the UK.

In what was also considered to have had an impact, the Queen told a well-wisher she hoped “people will think very carefully about the future” in the days before the vote.

The comment - from a monarch who has consistently stayed above politics - was considered as a benefit to those against independence.

“I accept that verdict of the people, and I call on all of Scotland to follow suit in accepting the democratic verdict of the people of Scotland.” - Scottish First Minister, Alex Salmond, reacting to the result at the time

A day after the referendum, Alex Salmond announced his resignation.

Worth noting: In the 2010 Westminster election, the Conservatives - despite only winning one seat Scottish seat - won the majority across the UK and went into power in a coalition with the Lib Dems.

BUT…BREXIT?

A “once in a generation” vote is hardly going to be back on the ballot box after seven years, right? Well, Brexit happened.

As you know, back in 2016 the UK was bitterly divided on the question of whether or not to leave the European Union. In the end, 52% voted in favour, while 48% were against.

England and Wales voted in favour, while both Northern and Ireland and Scotland were against.

In fact, Scotland was significantly opposed to the idea - 62% of its population wanted to stay with the EU.

An interesting study called ‘Is Brexit fuelling support for independence?’ looked at people’s views in Scotland on how they wanted to be governed - devolution vs independence.

The results showed 2016 was the first time since 1999 that a majority were in support of independence.

One of the key reasons the SNP now argue there are grounds for a second referendum is because by voting to stay in the UK in 2014, they indirectly ended up forced to leave the EU and single market in 2016.

The point is also made that many Scottish voters could have been swayed to vote against independence in 2014 solely due to a lack of certainty they’d be able to re-enter the EU.

Reacting to the Brexit result, Sturgeon said Scotland was leaving the EU “against our will,” adding “I regard that as democratically unacceptable”.

“And of course, we face that prospect less than two years after being told that it was our own referendum on independence that would end our membership of the European Union, and that only a rejection of independence could protect it. Indeed, for many people, the supposed guarantee of remaining in the EU was a driver in their decision to vote to stay within the UK.” - Sturgeon in 2016

Worth noting: An independent Scotland does not automatically mean entry back into the European Union. All of the current 27 member states would have to approve it.

Who would vote against it? Well, the answer to that is uncertain. Some experts have suggested Spain could face a difficult decision - whereby a vote against Scotland joining could be used to send a strong signal to pro-independence politicians in Catalonia.

Remember: Back in 2017, the Catalan government (the region where Barcelona is) held a referendum on independence that was never recognised. The Spanish government based in Madrid never gave approval for the referendum to go ahead, and while a majority voted in favour of independence, most who were against it didn’t even cast a vote.

COST OF INDEPENDENCE

Scotland spends more than it makes. Under a devolved government, Scotland still receives financial aid from the British government - a block grant - like in Northern Ireland.

Figures show Scotland spends more than £2,700 more than it makes per person.

There’s an argument amongst unionists that Scotland couldn’t afford to survive without this financial support.

In 2019/2020, Scotland’s revenue was 8% of the UK total. That same year, it accounted for roughly 9.2% of the UK’s expenditure - £81 billion.

In 2019, Scotland spent 8.6% more than it earned. This compares with 2.6% for the UK overall, according to The Economist.

Similar to the conversation about a united Ireland, there is much debate about the cost of an independent Scotland.

For example, in 2014 those against independence argued the Scottish would each be £1,400 worse off. The Yes campaign came up with completely different figures, saying people would gain £1,000 if it parted from the rest of the UK.

When it comes to more recent estimates, a Channel 4 News piece this month said Scotland exports “three times more to the UK than to the EU”. An expert on the programme predicted independence would be “around two to three times more costly to the Scottish economy than Brexit”.

A report from February of this year suggested an independent Scotland’s economy would shrink by “at least £11 billion a year”. It also projected Scotland’s economy would shrink by between 6.3% and 8.7% in the long run.

Does Scotland have natural resources? Yes. In the late 1960s oil was found off the coast of Scotland. That oil added around a £193 billion to the UK economy between 1975 and 2020.

An independent Scotland would be entitled to 91% of the UK’s oil based on geographical locations. In 2019, oil and gas was worth approximately £8.8 billion to Scotland’s economy - that’s 5% of its total GDP.

CALLING A REFERENDUM

Under the 1998 Scotland Act, the Scottish Government does not have the right to unilaterally call for a referendum. It states the makeup of the union is “reserved” to Westminster.

In a letter to Sturgeon in January 2020, Prime Minister Johnson said he would not transfer the power to call a new referendum to the Scottish parliament.

“You and your predecessor made a personal promise that the 2014 Independence Referendum was a ‘once in a generation’ vote… another independence referendum would continue the political stagnation that Scotland has seen for the last decade.”

Shortly after the election results over the weekend, Sturgeon said there is “no democratic justification whatsoever for Boris Johnson or anyone else seeking to block the right of the people of Scotland to choose our future.”

Sturgeon’s repeated goal is to have a referendum be held within the first half of this next parliamentary term. This would mean before autumn 2023, dependent on the pandemic being over.

In March of this year, the Scottish government brought forward a draft Independence Referendum Bill.

It proposes the Scottish Parliament should have the right to propose a date for a referendum, and that the same question should be asked as was in 2014 - “Should Scotland be an independent country?” with Yes and No options on the ballot paper.

Who would be able to vote? Any legal resident over the age of 16 can vote, regardless of their nationality, as long as they are on the electoral register. If you are in jail on a sentence of less than 12 months you would also be able to vote, according to the Institute for Government.

DISAGREEMENT FROM DOWNING STREET

In an interview with The Telegraph on Saturday, Prime Minister Johnson said a referendum “in the current context is irresponsible and reckless”.

“Well, as I say, I think that there’s no case now for such a thing … I don’t think it’s what the times call for at all.”

Speaking on Sky News on Sunday, Michael Gove said the conversation around another referendum was a “massive distraction” and not the key issue voters were concerned about.

Gove avoided directly answering repeated questions on whether or not the UK Government would take the Scottish Government to the Supreme Court if Sturgeon made a unilateral decision to hold a referendum.

Worth noting: An April poll showed independence was actually a top priority for Scottish voters, followed by education, the NHS, the economy and the pandemic.

What do Westminster and Holyrood actually agree on? A referendum on independence while the pandemic is ongoing is not on the cards.

IF INDEPENDENCE HAPPENED…

Well, what would then happen? A lot of questions remain unanswered, but some clarity was given back in 2014.

For example, during the campaign Alex Salmond suggested a vote for independence would lead to an 18-month negotiation period with the UK on key issues.

Salmond also expressed an intention to remain within the Commonwealth and keep the Queen as Head of State.

The Commonwealth’s secretary general at the time suggested an independent Scotland would need to reapply.

Money matters: A key question also would be what currency Scotland would adopt in the event of independence. A lot of comparisons are made to Ireland gaining independence in the early 1920s. For a few years after, Ireland stayed with the pound sterling. By 1927, the Irish pound was adopted right up until the change to the euro in 2002. For more than the first five decades, the Irish pound had a “fixed link” to sterling.

One of the critical changes between now and 2014 is, as already stated, Brexit.

If an independent Scotland was to successfully reapply to the European Union and rejoin the single market, the situation becomes even more complex.

Experts suggest customs officials would have to be stationed at the border with England.

POLITICS AND POLLING

It’s important to note that while a significant majority of the Scottish Parliament are in favour of independence, it does not necessarily portray the views of the Scottish people.

In a poll from April 19, 46% of Scots said they would prefer their country to vote against independence, while 45% wanted a vote to be in favour of it. When votes from across the UK were taken into account, 60% believe independence would make Scotland weaker.

The most recent poll (May 5) from Ipsos MORI showed an even split on independence - 50% in favour, 50% against.

One thing that is clear - the future of both Scotland and the UK will continue to be fiercely debated and defended.