🇲🇲 Myanmar: The Constant Struggle for Democracy

Morning all,

Today marks one year since Aung San Suu Kyi's political party was declared the winner of a fraught election in Myanmar - one that ultimately led to a coup.

Myanmar's most prominent figure is now once again under house arrest, and we felt it was an important time to gather some research on this, and the country in general, for those who want to know a little bit more.

Until Monday,

Your Fixers

OVERVIEW

Myanmar - sometimes referred to as Burma - is a country in mainland Southeast Asia, with a population of roughly 57 million.

The population is made up of more than 100 ethnic groups. However, Burmas form the majority of its population - 68% - and have traditionally dominated Burmese society, both politically and economically.

The vast majority - 88% - are Buddhist, and Burmese is the official language.

WHAT'S IN A NAME?

During its time as a British colony, the country's name was the Union of Burma. This was officially changed to the Union of Myanmar in 1989, by ruling military junta.

In Burmese, the country has been called 'Myanma' (or Mranma Prañ) since the 13th century. According to The BBC, Burma "is a local corruption of the word Myanmar".

"If Burmese people are writing for publication, they use 'Myanmar', but speaking they use 'Burma." - context from anthropologist Gustaaf Houtman

International positions: Countries like the US and the UK still refer to the country as Burma - so as not to accept the legitimacy of the regime.

This is because the year before the country's name change, thousands were killed in the suppression of a popular uprising.

The name change was recognised by many, including the UN, and is mostly the name used in media reports.

LET'S TAKE IT BACK - BRITISH COLONISATION

In 1885, after a third Anglo-Burmese war, Burma fell.

The country was colonised by the British, and incorporated into the British Raj - becoming a province of India. Under British rule, the monarchy was eliminated, and religion and government were separated, leading to a rise in secularism.

During the 1920s, protests against colonial rule gained momentum. This was led by a group of radical students at the University of Rangoon and became known as the Thakin movement. By 1930, protests had turned violent.

In 1936, protestors once again went on strike. These protests were led by a young man named Aung San - who later joined the Thakin movement.

He would go on to become a national hero - and his daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi, likewise an important figure.

Following this period of resistance, the British separated Burma from India, and granted it its own constitution in 1937.

AUNG SAN

During WWII, the British issued an arrest warrant for Aung San, and he subsequently escaped.

The Japanese made him an offer - they would grant Burma independence, if they had his help in overthrowing the British. Aung San received secret support and military training from the Japanese - but ultimately switched sides to the allies.

Both countries today have differing views on the historical connections between them - Japan credits itself with building the military that brought independence from Britain to the Burmese. Meanwhile, many in Burma look at it that they defeated efforts by both Japan and Britain to rule.

Anyway, back to Aung San...

In 1947, two years after the end of WWII, the British agreed to Burmese independence. That same year, Aung San, along with most of his cabinet, were assassinated, and a political rival was executed for orchestrating it.

A year after his death, in 1948, Burma did become independent.

Aung San became a national hero. Meanwhile, his wife became a politician and was appointed ambassador to India in 1960 - leaving Burma and taking her children, including Aung San Suu Kyi, to live and study abroad.

A COUP

Meanwhile in Burma, parliamentary democracy remained in place. However this ended in 1962, when General Ne Win staged a successful military coup. Ne Win had been in the Thakin movement, and was one of the 29 men recruited by Aung San - as well as his closest associate.

Ne Win combined a repressive military dictatorship with a socialist economic programme - following a policy of isolationism and state-controlled industry. However, by the early 1980s Burma’s economic situation was deteriorating - and the country, rife with corruption, was experiencing food shortages.

As the country’s situation deteriorated, Ne Win’s behaviour was becoming increasingly erratic. During the 1980s, he demonetised his country’s currency twice, wiping the savings of many citizens and making him deeply unpopular.

Many of his policies were also dictated by omens and astrology. To address economic issues, in 1987 he took 100, 75, 35 and 25 bills out of circulation - leaving just 45 and 90.

This was because those numbers were divisible by nine - and nine was his lucky number.

AUNG SAN SUU KYI

After living in India, Aung San Suu Kyi had gone on to study at Oxford University and settled in the UK, where she was married with two sons. However, in 1988 she returned to Burma to look after her mother who had suffered a stroke.

By coincidence that same year, on August 8 1988, huge student-led protests broke out against the government - coined the 888 uprising.

Some estimate that 3000 people died in the brutal crackdown, and protestors looked to 43-year-old Suu Kyi to emulate her father by fighting for the Burmese people and for democracy.

On August 26 1988, Suu Kyi did just that - standing before 500,000 people on the steps of the Shwedagon Pagoda and calling for democracy, whilst advocating for non-violent struggle.

General Saw Maung led a coup against the government and Ne Win stood down. A new military junta was created - called the State Law and Order Restoration Committee.

This new government said it would allow for a multi-party electoral system and in 1989 changed the country’s name to the Union of Myanmar. The Junta argued “burma” was remnant of the colonial era and favoured the Burma ethnic majority; “Myanmar” was more inclusive.

QUEST FOR DEMOCRACY

In preparation for a multi-party electoral system, Suu Kyi launched a political party - the National League for Democracy (NLD). She stayed in Burma despite being separated from her family.

However the military made her a political prisoner in 1989, she was put under house arrest and barred from elected office.

An election did go ahead in 1990, and the NLD won despite Suu Kyi’s arrest. However, the military refused to recognise the result and remained in power.

PERSONAL SACRIFICE

Suu Kyi remained committed to non-violent struggle, winning a Nobel Peace Prize in 1991. She was released in 1995 but her movement was restricted, and she was unable to leave the capital city.

In 1999, Suu Kyi’s husband was diagnosed with cancer - but the government would not allow him to travel to Myanmar. Instead, Suu Kyi was permitted to travel to the UK but did not go, for she feared she would be unable to return.

Her husband died that same year. Suu Kyi was arrested again in 2000 for defying the government and leaving the capital.

In 2002 Suu Kyi emerged from arrest for a second time - addressing her supporters - but was arrested for a third time in 2003, with the government extending her sentence on four occasions.

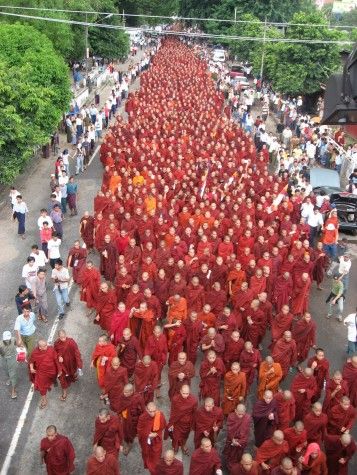

THE SAFFRON REVOLUTION

Amid rising fuel prices, the Saffron Revolution took place in 2007 (it called this because of the robes of the participating Buddhist monks).

The revolution prompted some change - and a new constitution was introduced in 2008 - paving the way for free elections.

The new constitution may have paved the way for elections, but it also stopped Suu Kyi from assuming the title of President. This is because both of her sons are British citizens.

It also gave the military widespread powers, even under civilian rule. They would hold 25% of seats in parliament - and if the constitution were to be changed, it would require over 75% of parliament to vote for it. It gave the military control of home affairs, defence and border affairs.

The first elections for more than 20 years were held in 2010, and the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) won by some distance.

Opposition parties and other countries described the election as fraudulent, with the military saying the election marked a transition to democracy. The Junta dissolved and a civilian parliament was put in place.

THE RELEASE OF AUNG SAN SUU KYI

Aung San may have been prevented from taking part in the 2010 election, but soon after was released from house arrest.

She immediately began working with her party the NLD to prepare for 2015 - the year of the next election, which it was hoped would be the first free election in 25 years.

THE 2015 ELECTION

In 2015 around 30 million people were eligible to vote, and turnout was estimated at about 80%. Aung San and the NLD won in a landslide - securing a majority in both the upper and lower houses of parliament.

Around the world, the result was viewed as a victory for democracy and for Myanmar.

A man called Htin Kyaw, a close associate of Suu Kyi, was appointed as Myanmar’s leader. Suu Kyi was unable to fill this position due to the 2008 constitution.

Instead, she was appointed as ‘state counsellor’ - a tailor-made position which allowed her to be leader in all-but-name.

CHANGING IMAGE

The victory of the NLD and its nobel prize-winning leader Suu Kyi may have been cause for celebration in some respects - but the election was only described as being “largely free”.

That is because certain minorities were unable to take part, including hundreds of thousands of the Rohingya - a predominantly muslim minority group.

This was not the fault of the NLD or Suu Kyi - Burma’s 1982 Citizenship Act excludes groups including the Rohingya. This effectively makes all belonging to this group stateless.

This pre-dates the NLD government - but the treatment of the Rohingya since 2015 has been described as “ethnic cleansing” - and has hugely tarnished Suu Kyi’s international reputation.

THE ROHINGYA

The Rohingya have been discriminated against in Myanmar for more than 50 years - with tensions beginning during WWII when the Rohingya and the majority Buddhist Burmans supported opposing sides.

Although the Rohingya’s lineage can be traced back to the 15th century, the government views the Rohingya as illegal immigrants - and the group has long been subjected to violence and discrimination.

Since 1991, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya have been displaced by military operations and fled to neighbouring Bangladesh.

In 2016, a Rohingya militant group called Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army emerged and in 2017 coordinated attacks on border police stations - killing 12 police officers.

The attack sparked a violent retaliation against civilians - leading to 400 deaths and the mass exodus of 400,000 Rohingya to Bangladesh. Since the attack, an estimated 210 villages have been burnt to the ground.

In 2016, it was also widely reported that the military were laying landmines near the Bangladesh border to prevent the Rohingya from returning. The events have been described by the UN’s human rights commissioner as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing”.

POLITICS AT PLAY

Aung San Suu Kyi has been condemned by the international community for allowing this to happen.

In a 2017 interview with the BBC she said;

"I don't think there's ethnic cleansing going on, I think ethnic cleansing is too strong an expression to use for what's happening."

She noted that in the constitution, military matters are to be left to the army - and if those who fled to Bangladesh returned, they would be safe.

That same year two Reuters journalists were arrested for investigating Rakhine state - and Suu Kyi chose not to pardon them, despite mounting international pressure. In 2018, Amnesty International stripped her of its highest honour - and some have called for her Nobel peace prize to be revoked.

While Suu Kyi has taken much criticism, it is of note that analysts have said that the military has continued to wield much control in this era of democracy.

One expert noted Suu Kyi tried to pacify the military by defending its abuse against the Rohignya and by restricting press freedoms.

THE NOVEMBER ELECTION

In November 2020, Suu Kyi and the NLD party won once again - securing enough seats to form a government. They offered ethnic minorities to work with it - an offer they did not make in 2015.

However, the military-backed USDP said it did not recognise the results of the election and accused the government of irregularities.

International observers such as Human Rights Watch deemed the election flawed because of Rohingya disenfranchisement, but there was little dispute that the NLD achieved a genuine overwhelming victory.

Discussion of yet another military coup began to circulate. In January 2021, Zaw Min Tun, Myanmar Defence Forces Spokesman said “we are not saying the military will take power, but we’re not saying it won't either”.

THE 2021 COUP

On February 1 2021, the military seized power in a coup, detaining Aung San Suu Kyi and other prominent politicians.

It announced General Min Aung Hlaing would take charge in a yearlong state of emergency.

Following the coup, Myanmar saw its largest protests since the Saffron Protests in 2007 - and has been marred in violence and unrest since. Some protestors have turned to armed resistance - with insurgents active in the country.

WHAT'S HAPPENING NOW?

Aung San Suu Kyi is currently being tried on corruption and other charges - which her supporters say are illegitimate.

A conviction would prevent her running in future elections.

Earlier this month, two of her close pro-democracy allies were jailed for a total of 165 years.

For the Rohingya, the outlook is bleak - this month the military was accused by Fortify Rights of committing war crimes - with their actions mirroring the build up to atrocities in 2017.

More than 100,000 people have been displaced in the ongoing fighting and reports of the military arresting humanitarian workers and destroying aid have emerged.

Freedom of speech continues to come under attack - and earlier this week US journalist Danny Fenster was sentenced to 11 years in jail.

A court found him guilty of multiple charges including incitement, and he is one of dozens of local journalists that have been detained since the coup.

*Quick update: In a surprise u-turn, Danny Fenster was released and allowed to leave Myanmar days after the sentencing.

We hope this serves as a helpful introductory piece to this topic so you can confidently engage in conversation about this ongoing, and very important, story.

Thank you for reading!

⏳